- Home

- Tim Winton

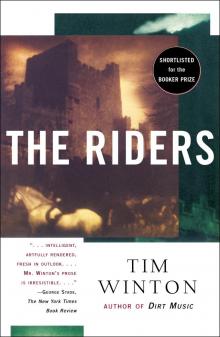

The Riders

The Riders Read online

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

for Denise

Wasted and wounded

It ain’t what the moon did

I got what I paid for now

See you tomorrow

Hey Frank can I borrow

A couple of bucks from you

To go

Waltzing Matilda

Waltzing Matilda

You’ll go waltzing Matilda with me . . .

Tom Waits, ‘Tom Traubert’s Blues’

I

On Raglan Road on an autumn day

I saw her first and knew

That her dark hair would weave a snare

That I may one day rue . . .

‘Raglan Road’ (traditional)

One

WITH THE NORTH WIND hard at his back, Scully stood in the doorway and sniffed. The cold breeze charged into the house, finding every recess and shadowy hollow. It rattled boards upstairs and lifted scabs of paint from the walls to come back full in his face smelling of mildew, turf, soot, birdshit, Worcestershire sauce and the sealed-up scent of the dead and forgotten. He scraped his muddy boots on the flagstones and closed the door behind him. The sudden noise caused an explosion in the chimney as jackdaws fled their fortress of twigs in the fireplace. His heart racing, he listened to them batter skyward, out into the failing day, and when they were gone he lit a match and set it amongst the debris. In a moment fire roared like a mob in the hearth and gave off a sudden, shifting light. The walls were green-streaked, the beams overhead swathed in webs and the floor swimming with trash, but he was comforted by the new sound and light in the place, something present besides his own breathing.

He simply stood there firestruck like the farmboy of his youth, watching the flames consume half-fossilized leaves and twigs and cones. There in the blaze he saw the huge burns of memory, the windrows of uprooted karris whose sparks went up like flares for days on end over the new cleared land. The walls here were a-dance now, and chunks of burning soot tumbled out onto the hearthstone. Scully jigged about, kicking them back, lightheaded with the stench and the thought of the new life coming to him.

The chimney shuddered, it sucked and heaved and the rubbish in the house began to steam. Scully ran outside and saw his new home spouting flame at the black afternoon sky, its chimney a torch above the sodden valley where his bellow of happiness rang halfway to the mountains. It really was his. Theirs.

• • •

IT WAS A SMALL HOUSE, simple as a child’s drawing and older than his own nation. Two rooms upstairs, two down. Classic vernacular, like a model from the old textbooks. It stood alone on the bare scalp of a hill called the Leap. Two hundred yards below it, separated by a stand of ash trees and a hedged lane was the remains of a gothic castle, a tower house and fallen wings that stood monolithic above the valley with its farms and soaklands. From where Scully stood, beneath his crackling chimney, he could see the whole way across to the Slieve Bloom Mountains at whose feet the valley and its patchwork of farms lay like a twisted shawl. Wherever you looked in that direction you saw mountains beyond and castle in the corner of your eye. The valley squeezed between them; things, colours, creatures slipped by in their shadow, and behind, behind the Leap there was only the lowest of skies.

He wasted no time. In what remained of the brief northern day he must seal the place against the weather, so he began by puttying up loose windowpanes and cutting a few jerry-built replacements out of ply. He dragged his tools and supplies in from the old Transit van and set a fallen door on two crates to serve as a workbench. He brought in a steel bucket and a bag of cement, some rough timber, a few cans of nails and screws and boxes of jumbled crap he’d dragged halfway round Europe. By the fire he stood a skillet and an iron pot, and on the bench beside some half-shagged paperbacks he dropped his cardboard box of groceries. All the luggage he left in the van. It was a leaky old banger but it was drier and cleaner than the house.

He lined up his battered power tools along the seeping wall nearest the fire and shrugged. Even the damp had damp. The cottage had not so much as a power point or light socket. He resigned himself to it and found a trowel, mixed up a slurry of cement in his steel bucket, stood his aluminium ladder against the front wall and climbed up onto the roof to caulk cracked slates while the rain held off and the light lasted. From up there he saw the whole valley again: the falling castle, the soaks and bogs, the pastures and barley fields in the grid of hawthorn hedges and drystone walls all the way up to the mountains. His hands had softened these past weeks. He felt the lime biting into the cracks in his fingers and he couldn’t help but sing, his excitement was so full, so he launched rather badly into the only Irish song he knew.

There was a wild Colonial boy,

Jack Dougan was his name . . .

He bawled it out across the muddy field, improvising shamelessly through verses he didn’t know, and the tension of the long drive slowly left him and he had the automatic work of his hands to soothe him until the only light was from the distant farmhouses and the only sound the carping of dogs.

By torchlight he washed himself at the small well beside the barn and went inside to boil some potatoes. He heaped the fire with pulpy timber and the few bits of dry turf he found, and hung his pot from the crane above it. Then he lit three cheap candles and stood them on a sill. He straightened a moment before the fire, feeling the day come down hard on him. It was sealed now. It was a start.

He put one boot up on a swampy pile of the Irish Times and saw beside his instep:

BOG MAN IN CHESHIRE

Peat cutters in Cheshire yesterday unearthed the body of a man believed to have been preserved in a bog for centuries . . .

Scully shifted his foot and the paper came apart like compost.

It was warm inside now, but it would take days of fires to dry the place out, and even then the creeping damp would return. Strange to own a house older than your own nation. Strange to even bother, really, he thought. Nothing so weird as a man in love.

Now the piles of refuse were really steaming and the stink was terrible, so with the shovel and rake, and with his bare hands, he dragged rotten coats and serge trousers, felt hats, boots, flannel shirts, squelching blankets, bottles, bicycle wheels, dead rats and curling mass cards outside to the back of the barn. He swept and scraped and humped fresh loads out to the pile behind the knobbly wall. The norther was up again and it swirled about in the dark, calling in the nooks of the barn. Stumbling in the gloom he went to the van for some turps, doused the whole reeking pile and took out his matches. But the wind blew and no match would light, and the longer he took the more he thought about it and the less he liked the idea of torching the belongings of a dead man right off the mark like this. He had it all outside now. The rest could wait till morning.

Somewhere down in the valley, cattle moaned in their sheds. He smelled the smoke of his homefire and the earthy steam of boiling spuds. He saw the outline of his place beneath the low sky. At the well he washed his numb hands a second time and went indoors.

When the spuds were done he pulled a ruined cane chair up to the hearth and ate them chopped with butter and slabs of soda bread. He opened a bottle of Guinness and kicked off his boots. Five-thirty and it was black out there and had been the better part of an hour. What a hemisphere. What a day. In twenty-eight hours he’d seen his wife and daughter off at Heathrow, bought the old banger from two Euro-hippies at Waterloo Station, retrieved his tools and all their stored luggage fr

om a mate’s place in North London and hit the road for the West Coast feeling like a stunned mullet. England was still choked with debris and torn trees from the storms and the place seemed mad with cops and soldiers. He had no radio and hadn’t seen a paper. Enniskillen, people said, eleven dead and sixty injured in an IRA cock-up. Every transfer was choked, every copper wanted to see your stuff. The ferry across the Irish Sea, the roads out of Rosslare, the drive across Ireland. The world was reeling, or perhaps it was just him, surprised and tired at the lawyer’s place in Roscrea, in his first Irish supermarket and off-licence. People talked of Enniskillen, of Wall Street, of weather sent from hell, and he plunged on drunk with fatigue and information. There had to be a limit to what you could absorb, he thought. And now he was still at last, inside, with his life back to lock-up stage.

The wind ploughed about outside as he drank off his Guinness. The yeasty, warm porter expanded in his gut and he moaned with pleasure. Geez, Scully, he thought, you’re not hard to please. Just look at you!

And then quite suddenly, with the empty bottle in his lap, sprawled before the lowing fire in a country he knew nothing about, he was asleep and dreaming like a dog.

Two

SCULLY WOKE SORE AND FREEZING with the fire long dead and his clothes damp upon him. At the well he washed bravely and afterwards he scavenged in his turp-soaked rubbish heap and found a shard of mirror to shave by. He wiped the glass clean and set it on the granite wall. There he was again, Frederick Michael Scully. The same square dial and strong teeth. The broad nose with its pulpy scar down the left side from a fight on a lobster boat, the same stupid blue that caused his wonky eye. The eye worked well enough, unless he was tired, but it wandered a little, giving him a mad look that sometimes unnerved strangers who saw the Brillopad hair and the severely used face beneath it as ominous signs. Long ago he’d confronted the fact that he looked like an axe-murderer, a sniffer of bicycle seats. He stuck out like a dunny in a desert. He frightened the French and caused the English to perspire. Among Greeks he was no great shakes, but he’d yet to find out about the Irish. What a face. Still, when you looked at it directly it was warm and handsome enough in its way. It was the face of an optimist, of a man eager to please and happy to give ground. Scully believed in the endless possibilities of life. His parents saw their lives the way their whole generation did; to them existence was a single shot at things, you were a farmer, a fisherman, a butcher for the duration. But Scully found that it simply wasn’t so. It only took a bit of imagination and some guts to make yourself over, time and time again. When he looked back on his thirty years he could hardly believe his luck. He left school early, worked the deck of a boat, went on to market gardening, sold fishing tackle, drove trucks, humped bricks on building sites, taught himself carpentry and put himself through a couple of years’ architecture at university. Became a husband and father, lived abroad for a couple of years, and now he was a landowner in County Offaly, fixing an eighteenth-century peasant cottage with his bare hands. In the New Year he’d be a father again. Unbelievable. All these lives, and still the same face. All these goes at things, all these chances, and it’s still me. Old Scully.

He was used to being liked and hurt at being misunderstood, though even in Europe most people eventually took to Scully. What they saw was what they got, but they could never decide what it was they saw – a working-class boofhead with a wife who married beneath herself, a hairy bohemian with a beautiful family, the mongrel expat with the homesick twang and ambitious missus, the poor decent-hearted bastard who couldn’t see the roof coming down on his head. No one could place him, so they told him secrets, opened doors, called him back, all the time wondering what the hell he was up to, slogging around the Continent with so little relish. Children loved him; his daughter fought them off outside crèches. He couldn’t help himself – he loved his life.

As mist rolled back from the brows of the Slieve Bloom Mountains, the quilted fields opened to the sun and glistened with frost. Scully swung the mattock in the shadows of the south wall. The earth was heavy and mined with stones so that every few strokes he struck granite and a shock went up his arm and into his body like a boot from the electric fences of his boyhood. His hands stung with nettles and his nose ran in the cold. The smoke of valley chimneys stood straight in the air.

In the hedge beside him two small birds wheeled in a courting dance. He recognized them as choughs. He mouthed the word, resting a moment and rubbing his hands. Choughs. Strange word. Two years and he still thought from his own hemisphere. He knew he couldn’t keep doing it forever. He should stop thinking of blue water and white sand; he had a new life to master.

The birds lit on an old cartwheel beside the hedge to regard him and the great pillar of steam his breath made.

‘It’s alright for you buggers,’ he said. ‘The rest of us have to work.’

The choughs lifted their tails at him and flew. Scully smiled and watched them rise and tweak about across the wood below, and then out over the crenellations of the castle beyond where he lost them, his eye drawn to the black mass of rooks circling the castle keep. A huge ash tree grew from the west wing of the ruin and in its bare limbs he saw the splotches of nests. He tried to imagine that tree in the spring when its new foliage must nearly burst the castle walls.

He went back to his ragged trench against the cottage wall. The place had no damp-coursing at all, and the interior walls were chartreuse with mildew, especially this side where the soil had crept high against the house. The place was a wreck, no question. Ten years of dereliction had almost done for it. The eastern gable wall had an outward lean and would need buttressing in the short term at least. He had neither power nor plumbing and no real furniture to speak of. He’d have to strip and seal the interior walls as soon as he could. He needed a grader to clear centuries of cow slurry from the barnyard and a fence to keep the neighbours’ cattle out of his modest field. He needed to plant trees – geez, the whole country needed to plant them – and buy linen and blankets and cooking things. A gas stove, a sink, toilet. It hardly bore thinking about this morning. All he could manage was the job at hand.

Scully went on hacking the ground, cursing now and then and marvelling at how sparks could still be made off muddy rocks.

He thought of the others, wondered how long he would have to be alone. He wasn’t the solitary sort, and he missed them already. He wondered how Jennifer and Billie would cope seeing Australia again. Hard to go back and go through with leaving it forever. He was glad it was them. Himself, he would have piked out. One foot on the tarmac, one sniff of eucalyptus and he’d be a goner. No, it was better they went and finished things up. He was best used to get things ready here. This way he could go through with it. Scully could only feel things up to a certain point before he had to act. Doing things, that’s what he was good at. Especially when it had a point. This was no exception. He was doing it for Jennifer, no use denying it, but she appreciated what it had taken for him to say yes. It was simple. He loved her. She was his wife. There was a baby on the way. They were in it together, end of story.

He worked all day to free the walls of soil and vegetation, pulling ivy out of the mortar when the mattock became too much. He ran his blistered hands over the old stones and the rounded corners of his house and smiled at how totally out of whack the whole structure was. Two hundred and fifty years and probably not a single stone of it plumb.

Ireland. Of all places, Ireland, and it was down to Mylie Doolin, that silly bugger.

Scully had originally come to the Republic for a weekend, simply out of respect. It was the country boy in him acknowledging his debts, squaring things away. They were leaving Europe at last, giving in and heading home. It seemed as though getting pregnant was the final decider. From Greece they caught a cheap flight to London where they had things stored. The Qantas flight from Heathrow was still days away, but they were packed and ready so early they went stir crazy. In the end, Scully suggested a weekend in Ireland. They’d

never been, so what the hell. A couple of pleasant days touring and Scully could pay his respects to Mylie Doolin who had kept the three of them alive that first year abroad.

Fresh off the plane from Perth, Scully worked for Mylie on dodgy building sites all over Greater London. The beefy Irishman ran a band of Paddies on jobs that lacked a little paperwork and needed doing quick and quiet for cash money. On the bones of his arse, Scully found Mylie’s mob in a pub on the Fulham Road at lunchtime, all limehanded and dusthaired and singing in their pints. The Paddies looked surprised to see him get a lookin, but he landed an afternoon’s work knocking the crap out of a bathroom in Chelsea and clearing up the rubble. He worked like a pig and within a few days he was a regular. Without that work Scully and Jennifer and Billie would never have survived London and never have escaped its dreary maw. Mad Mylie paid him well, told him wonderful lies and set them up for quite some time. Scully saved like a Protestant. He never forgot a favour. So, only a weekend ago now, Scully had driven the three of them across the Irish midlands in a rented Volkswagen to the town of Banagher where, according to Mylie, Anthony Trollope had invented the postal pillar box and a Doolin ancestor had been granted a papal annulment from his horse. That’s how it was, random as you please. A trip to the bogs. A missed meeting. A roadside stop. A house no one wanted, and a ticket home he cashed in for a gasping van and some building materials. Life was a bloody adventure.

He worked on till dark without finishing, and all down the valley, from windows and barns and muddy boreens, people looked up to the queer sight of candles in the bothy window and smoke ghosting from the chimney where that woollyheaded lad was busting his gut looking less like a rich American every day.

Three

An Open Swimmer

An Open Swimmer Human Torpedo

Human Torpedo The Boy Behind the Curtain

The Boy Behind the Curtain Scission

Scission Eyrie

Eyrie Island Home

Island Home Scumbuster

Scumbuster The Turning

The Turning Legend

Legend Blueback

Blueback Signs of Life

Signs of Life Breath

Breath Land's Edge

Land's Edge Cloudstreet

Cloudstreet The Riders

The Riders Minimum of Two

Minimum of Two Shallows

Shallows The Shepherd's Hut

The Shepherd's Hut In the Winter Dark

In the Winter Dark